Early April, 2020

I had a moment of quarantine panic the other day.

I was making a loaf of bread, and when I took the top off the little wooden salt cellar that I keep by the stove, I saw that it was almost empty. So I got out the step-stool and reached up on the top shelf of the pantry where the refill box lives, but it wasn’t there. I started shifting all the plastic cereal containers around, thinking maybe it got pushed back behind them. I then moved all the boxes of staples on the next shelf down – flour, sugar, oats, quinoa – looking behind each one. With every box, my hands searched a little faster.

Who moved my salt‽

I go out into the garage to check our “extended pantry” shelves. Nothing. Back inside, I repeated entire process again. Twice.

OhmygoshOhmygoshOhmygosh. I have everything else. I thought we were Prepared. I made Lists.

Breathe.

People have fought wars over salt.

Breathe.

But you can’t just buy salt right now. Or flour. Or toilet paper. Or quarter-inch elastic at the fabric store.

Breathe.

A few weeks ago, my youngest daughter asked me if I’d ever experienced anything like this in my lifetime. This Pandemic. I told her the closest I’d ever come to it was a story my granddad told me once about the Spanish flu epidemic.

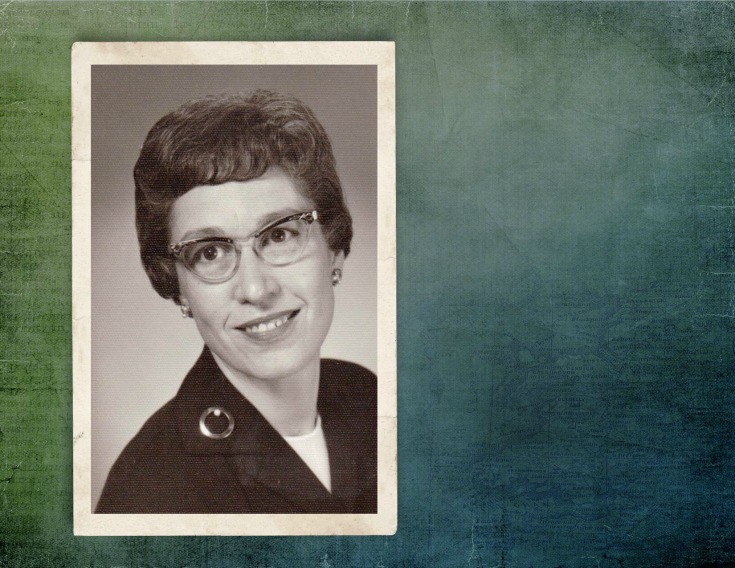

Like many young men of his time, Pop graduated early from high school in the winter of 1917-18, joined the Navy, and left directly for basic training. From there, he was sent on to Georgia for deployment, expecting to ship out and join his chums in Europe to fight in the War to End All Wars.

Most of the time, if Pop mentioned his hitch in the Navy at all, it was just to say, “I sure did enjoy being down South with all them sweet Georgia peaches,” and then he’d smile, and wink at whoever was listening. One time though, when I was in my late teens, Pop and I were sitting at the kitchen table, and I asked him what the worst thing was he’d ever seen in his life.

Pop didn’t hesitate. “You know,” he said, “when I was in the Navy in down in Georgia, we never even made it onto the gangway. I was always so disappointed I never got to go to Europe. See, the Spanish flu was sweeping through the South at that time and hitting the military boys hard, and we couldn’t take it on a ship, so we were stuck there in camp.

Once, after we’d been holed-up a couple of weeks, an officer gave me a packet to deliver across camp to the Infirmary. It was the dead of winter. Bone cold. Gawd, it was cold. Anyway, I’d never been inside the building he sent me to before. It was a huge quonset hut – you know, one of those half-moon metal military jobs – big enough to park ten tanks in.

“I walked up to the door on the end and knocked, and when the fellow inside opened it, I looked over his shoulder and all I could see from one end to the other were waves of heavy brown oil cloth, some as high as my chest, one wave rolling right into the next. I knew right away what they were. It was all those boys who’d been dying of Spanish flu, stacked up like cordwood, shrouded under all that canvas. The ground was froze solid and there was no way to bury them.”

He looked up at me. Then Pop and I sat there staring at the yellow Formica for a long time.

Wait. I know we have some salt.

I open the cupboard doors and start checking the seasoning shelves. (Yes. Shel-ves. I have a lot of seasonings.)

Garlic salt. Celery salt. Pink Himalayan Salt. Celtic Sea salt. Red Hawaiian salt. Greek seasoning. Old Bay. Lawry’s. Fine sea salt. I start pulling salts off the shelf and stacking them on the counter.

Fine sea salt.

Pop was an electrician. A lineman. He climbed impossibly tall electrical poles all day long in his thick denim jacket and heavy work boots. When I was little, he was still working lines in Portland; a loyal member of IBEW Local 48. He used to give me his little round union pins after every meeting.

Each workday, Pop would pack his lunch and fill his thermos with the thickest, blackest coffee you’ve ever seen. Inside his heavy metal lunch pail, he always kept a paper napkin, a clean handkerchief, and a small, navy and yellow saltshaker about the size of a twenty-nickel stack, with a picture of the Morton salt girl on the front.

Fine sea salt.

I hold the container of fine sea salt to my chest and look out at my little collection of salts on the counter. My heart rate begins to slow. The image of the little salt girl calms me.

According to Morton, she (the little salt girl) is about eight years old, and though she has never had an official name, I’ve always called her Sally, because until I was four or five, she sported two bright yellow braids and looked like Dick and Jane’s little sister in my older brother’s readers.

Sally the Salt Girl made her debut in 1911, four years before the beginning of the Spanish Flu epidemic. Since then, she has survived at least two major flu pandemics, polio, two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, disco, and multiple wars in the Middle East. This is not her first rodeo.

Don’t we have a box of leftover pickling salt? I’m sure we do.

I go out to check the garage shelves. Again.

Yep. There it is, stuck behind the boxed pasta: an almost full box of pickling salt, leftover from the last time we made dill pickles. The box is heavy in my hand: a salt brick, solid as a rock.

Hold up: can I use pickling salt in place of regular salt? What makes it pickling salt?

Now, prepare to either slap your forehead in disbelief that someone could live as long as I have and not gotten the Morton tag line, or prepare to have your mind blown. It will be one or the other. There is no in-between.

Ready?

When it rains, it pours.

OK. So unlike “table salt,” pickling salt (as I recently learned) is simply salt that does not contain anti-caking ingredients or additives like iodine. And because it lacks these anti-caking properties, pickling salt can turn into a solid brick, especially in humid or rainy conditions: my box of pickling salt being a case in point. Table salt, on the other hand, has additives that keep it from caking, so it will stay granular and pour smoothly,

– – – – – – even when it rains.

Apparently, prior to the early 1900s, housewives regularly had literally chisel their salt apart to use it, so having a salt that was guaranteed to pour in adverse weather conditions was a big deal. (Salt that pours when you want it to: just one more thing I have taken for granted all these years.)

When it rains, it pours.

By the mid-fifties, however, Sally’s catchy little slogan had taken on new meaning. Instead of simply describing the unique properties of a mundane kitchen staple, it came to suggest an existential axiom; that when bad things happen, more of the same are apt to follow. Personally, I’ve never bought into that concept: the implied fatalism goes against everything I believe.

I guess it all boils down to how you see the rain.

When I was eight, half my life was spent splashing through puddles in big rubber galoshes that covered my school shoes and came up almost to my knees. The Little Morton Salt Girl of my era, in her swing coat and dark bob, was me. We danced in the mud puddles. We dropped rocks to watch the rings ripple out to the edges and bounce back, one after the other. We inhaled the scent of early morning petrichor like a fresh marionberry pie.

It is that puddle-stomping little girl who comes to me now, comforting me; reminding me that this story isn’t about the rain. It’s about slogging through and doing what needs to be done, even as the rain pours down.

![Family Mugs [Illustration by Renee Butcher]](https://reneebutcher.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/mugs-4.1.jpg)